this post was submitted on 05 Jan 2024

1069 points (95.9% liked)

memes

17550 readers

3157 users here now

Community rules

1. Be civil

No trolling, bigotry or other insulting / annoying behaviour

2. No politics

This is non-politics community. For political memes please go to !politicalmemes@lemmy.world

3. No recent reposts

Check for reposts when posting a meme, you can only repost after 1 month

4. No bots

No bots without the express approval of the mods or the admins

5. No Spam/Ads/AI Slop

No advertisements or spam. This is an instance rule and the only way to live. We also consider AI slop to be spam in this community and is subject to removal.

A collection of some classic Lemmy memes for your enjoyment

Sister communities

- !tenforward@lemmy.world : Star Trek memes, chat and shitposts

- !lemmyshitpost@lemmy.world : Lemmy Shitposts, anything and everything goes.

- !linuxmemes@lemmy.world : Linux themed memes

- !comicstrips@lemmy.world : for those who love comic stories.

founded 2 years ago

MODERATORS

you are viewing a single comment's thread

view the rest of the comments

view the rest of the comments

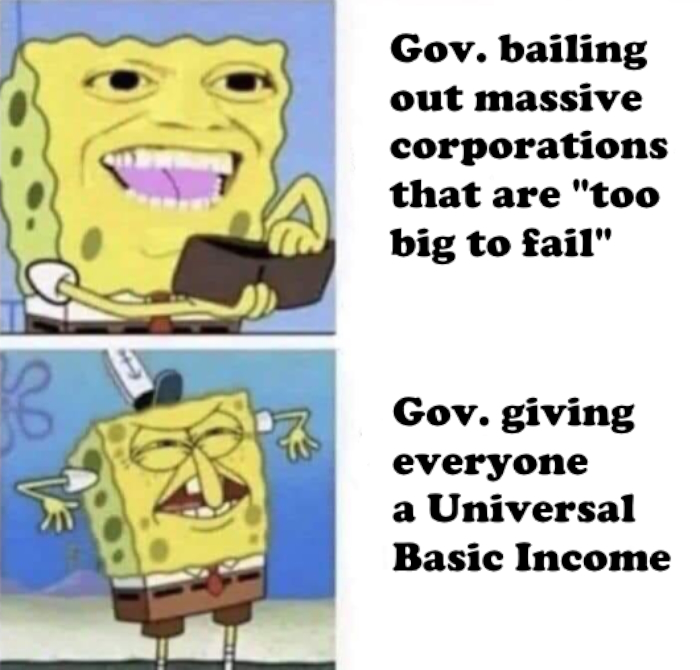

Disclosure: I don’t have an econ degree either

I don’t think that mechanism you’re referring to automatically finds its new equilibrium right back where you started.

Let’s take rent for instance. All the current renters in lowest income bracket now have $1000/mo more to spend.

Next income bracket up now has $800 more to spend. Not because the UBI is varying, but because the tax people are paying into the UBI is varying. So this next bracket up is putting $200 into it as taxes and getting their $1000 check. At a certain point, there are the people who break even. And above that, people are paying more into the system than they’re getting back. That’s worth mentioning.

But focusing on this lowest income bracket as if it’s a little segmented, separate economy. Like a slice, to analyze it.

Town with 100 people. Let’s say there’s 105 units of housing, making for a teeny bit of pressure on landlords via competition. The landlords live elsewhere; ultra simple model here. Each of the 100 people gets $1000 more to spend. Fuck it, all they’re spending it on is rent. It’s the only thing they have to buy.

Well, there’s still competition between the landlords. If a landlord’s got an empty unit, he can offer it for $200 less than the other guy and get a tenant in there. Excess supply is good for consumer negotiating power.

But also, let’s say all units just go up by $1000/mo, and swallow up the UBI.

Then other developers now have a new equation in terms of the costs and benefits of building new housing.

Maybe now that you can charge $1500 for an apartment instead of $500, it’s worth it to build a new apartment building. It’s become more profitable.

So someone builds a new apartment building, and there’s 120 housing units for those 100 renters. Now you’ve got 20 desperate landlords (or one landlord with 20 un-rented units) willing to take say $1000 instead of $1500.

That pushes the price of rent back down.

Of course it doesn’t actually sway wildly like this. Every player thinks ahead about all the moves that can be made.

Like if your apartment building is profitable at $1500 but not at $500, what’s the cutoff? Maybe if rents drop below $1200 your new apartment building is going to lose money.

There’s some equilibrium point, and that’s what the market price settles into, as people finding themselves far from that point find it profitable to move toward it. (You make more money renting out five units at $1000 than you make renting out two units at $1500 - lowering the price is profitable here).

So now to crack this model open again, what is this “other place” where these landlords are coming from to invest new money in housing?

That’s where we bring in the higher income tiers, the ones who pay more into UBI than they receive out. The money is coming from up there. In those places, the people have less money than they did before, and so it is becoming less profitable to fulfill their needs. Maybe the amount you can get for a luxury apartment in manhattan drops from $50k to $49k per month.

Ultimately, resources used to fulfill demands, get slowly and steadily re-allocated to serve money’s new center of gravity, which is slightly lower than before.

Prices go up for poor people goods, but not enough to eat all the income. And the new amount of money flowing improves the offering, even at the same price levels, by bringing more investment overall into those industries.