Discussion in the Matrix reading group (see this post for instructions on how to join) Saturday/Sunday of week 4, and anyone who'd rather discuss the text here can do so instead (a few questions will be posted here as well)

If anyone wants a reminder on the weekend for this and/or future discussions, mention it in the comments

Primarily for those who don't already have a discussion group, but anyone interested in Marxist-Leninist theory is welcome 👍

It won't require intensive reading/listening; it should be doable for anyone who works or studies full time, and we usually have discussions at the end of every other week. We're currently following a study plan from China, but we can add recommended texts (decided by vote). At the time of writing we're reading "Wage Labour and Capital" but I'm not going to remember to update this post

You can join the group at #reading-group:genzedong.xyz (an encrypted room) through the GenZedong Matrix space (see this post). There'll also be a pinned post in this community for the current text, for those who don't want to join the Matrix space.

(See first post for background: #1 Cultural Revolution, previous post: #5 Rise of First KMT-CPC Cooperation and Climax of the Great Revolution)

A Concise History of the Communist Party of China (2021, ISBN 978-7-5117-3978-0), pg. 30-35

《中国共产党简史》, pg. 25-28

(Chapter 1)

5. The Northern Expedition and the Worker and Peasant Movements

The Victorious March of the Northern Expedition

In July 1926, the National Revolutionary Army launched the Northern Expedition. The direct targets of the expedition were the imperialist-backed Northern Warlords, mainly Wu Peifu, Sun Chuanfang, and Zhang Zuolin, who had 700,000 troops under their direct control. The National Revolutionary Army under the Nationalist Government totaled around 100,000 men.

Vastly outnumbered, the NRA, under the guidance of Soviet advisors, opted for a strategy of concentrating its forces to eliminate enemy units one by one. With strong support from the locals along the way, the Northern Expeditionary Army won sweeping victories. In September, the army occupied Hanyang and Hankou. On October 10, it conquered Wuchang and wiped out the main force of Wu Peifu. The Army in Jiangxi eliminated the main force of Sun Chuanfang and occupied Jiujiang and Nanchang in early November. It seized Fuzhou in Fujian Province without a fight in December. The Army then made a plan to seize Zhejiang and Shanghai and gather its forces in Nanjing. In February 1927, it occupied Hangzhou and the whole province of Zhejiang. In March, it occupied Anqing and Nanjing and entered Shanghai. By this time, the Northern Expeditionary Army held all of the areas south of the Yangtze River.

While the Northern Expeditionary Army was building a tremendous victory, the Feng Yuxiang-led National Army, with the help of the Soviet Union and the CPC, moved south in September 1926, after taking a mass pledge in Wuyuan County, Suiyuan. In November, they took control of Shaanxi and Gansu provinces and prepared to move eastward out of Tongguan in support of the Northern Expeditionary Army.

The Northern Expedition was carried out under the anti-imperialist and anti-warlord slogans of the Communist Party. During the march of the Northern Expedition, members of the CPC and the Communist Youth League put their lives at risk and played a pioneering role, especially the independent regiment led by CPC member Ye Ting. The regiment, the first to enter Wuchang, matured into a heroic and battle-hardened unit of the Fourth Army, which was known as the “Iron Army.” The Communists made great contributions to the army’s political work and efforts to mobilize workers and peasants. Under the leadership of the Guangdong Regional Party Committee, the Guangzhou-Hong Kong Strike Committee of Guangdong organized 3,000 men into transport, propaganda, and medical teams to follow the troops north. The CPC Hunan Regional Committee mobilized workers and peasants to act as guides, deliver messages, transport equipment, and give medical aid. The committee also organized peasant self-defense corps to join in the fighting. Such enthusiasm was rarely seen in previous wars in China.

The great success achieved by the Northern Expedition in a short period of time was attributable to the cooperation between the KMT and the CPC.

The Upsurge of the Worker and Peasant Movements in Hunan, Hubei, and Jiangxi

After the victorious march of the Northern Expedition, the worker and peasant movements expanded at an unprecedented scale. The most remarkable developments occurred in Hunan, Hubei, and Jiangxi provinces.

It was in these provinces that the peasant movement first rose to prominence. In November 1926, Mao Zedong became the secretary of the Peasant Movement Committee of the CPC Central Committee. The peasant movements in Hunan, Hubei, Jiangxi, and Henan were the main focus of Mao’s work. From the summer of 1926 to January of the following year, the membership of peasant associations surged from 400,000 to 2 million in Hunan. Once the peasants were organized, they started to take action, launching an unprecedented rural revolution. As Mao Zedong pointed out at the time, “The national revolution requires a great change in the countryside. The Revolution of 1911 did not bring about this change, hence its failure. This change is now taking place, and it is an important factor for the completion of the revolution.”

Landlords, gentry, and the KMT right-wing were horrified by the flourishing peasant movement. They attacked the movement, labeling it a “movement of riffraff” and “utterly appalling!” At the beginning of 1927, Mao Zedong conducted a 32-day investigation into the peasant movement in Hunan. In his subsequent “Report on an Investigation of the Peasant Movement in Hunan,” he sharply refuted various fallacies inside and outside the CPC condemning the movement. He discussed the great significance of the rural revolution, and argued that all revolutionaries should stand in front of the peasants and lead them, not stand behind them and criticize them, much less stand opposite to them and oppose them. He emphasized that the Party should rely on the poor peasants, who were the “vanguard of the revolution” and unite with the middle peasants and other forces that could be won over. The Party should work to establish peasant associations and peasant armed forces so that the peasant associations could take over all the power in the countryside. Then they should reduce rents and interest and redistribute the land.

In the cities, the worker movement was also on the rise. In September and October 1926, the Hunan and Hubei provincial federations of trade unions were established. By January 1927, there were 700,000 union members in the two provinces. The Jiangxi Provincial Federation of Trade Unions was also formally established. These three provinces applied the experience of Guangzhou-Hong Kong Strike to organize armed workers’ pickets. In Changsha, Wuhan, Jiujiang, and other cities, workers held large-scale strikes, most of them successful. With the mass anti-imperialist struggle in full swing, the Nationalist Government was prompted to take back the British Concessions in Hankou and Jiujiang in February 1927.

Encouraged by the victorious advance of the Northern Expedition and the upsurge of the worker and peasant movements, the CPC Central Committee and Shanghai Regional Committee began in October 1926 to organize armed uprisings involving Shanghai workers. The first two were defeated. Thereafter, the CPC Central Committee and Shanghai Regional Committee jointly established a supreme body to command the uprisings. Known as the Special Committee, its members were Chen Duxiu, Luo Yinong, Zhao Shiyan, Zhou Enlai, with Zhou also serving as chief commander. Under its direct leadership, the Shanghai workers successfully staged a third armed uprising on March 21, 1927. On the 22nd, the Provisional Municipal Government of Shanghai Special City was established. It was the first revolutionary regime to be established by the people in a major city under CPC leadership.

The third armed uprising of the Shanghai workers was a major feat of the Chinese workers’ movement during the Great Revolution and the culmination of the movement’s development during the Northern Expedition.

(See first post for background: #1 Cultural Revolution, previous post: #4 Founding of CPC and Creation of Platform of Democratic Revolution)

A Concise History of the Communist Party of China (2021, ISBN 978-7-5117-3978-0), pg. 23-30

《中国共产党简史》, pg. 19-24

(Chapter 1)

4. The Rise of the First KMT-CPC Cooperation and the Climax of the Great Revolution

The Third National Congress of the CPC and the Establishment of KMT-CPC Cooperation

Chinese Communists saw from the failure of the Beijing-Hankou Railway strike that revolutionary forces in China were far less powerful than their imperialist and feudal counterparts. The CPC recognized the importance of forming the broadest possible united front. It thus decided to take positive steps to unite with the Kuomintang (KMT), which was led by Sun Yat-sen.

At that time, Sun Yat-sen had become disheartened by a series of setbacks resulting from his policy of relying on warlords to fight warlords. Having witnessed the influence of the CPC-led workers’ movement, Sun saw that it was an emerging and vibrant revolutionary force that he must cooperate with. In January 1923, the Executive Committee of the Communist International issued the Resolution on the Relationship between the Communist Party of China and the Kuomingtang, which gave support for cooperation between the two parties.

The Third National Congress of the CPC was held in Guangzhou in June 1923. The Congress was attended by more than 30 delegates, representing 420 CPC members.

The Congress made an accurate assessment of Sun Yat-sen’s revolutionary position and the possibility of reorganizing the KMT, and decided that CPC members should join the KMT in an individual capacity in order to realize cooperation with it. It was clearly stipulated that while Party members were to join the Kuomintang as individuals, the Party itself should maintain its political, ideological, and organizational independence.

At the Congress, the Party’s Constitution, adopted at the Second Congress, was revised for the first time to stipulate that those who wished to join the Party must complete a probationary period and that members may withdraw from the Party of their own free will.

The Congress elected a Central Executive Committee and set up the Central Bureau, of which Chen Duxiu was chairman.

After the Congress, KMT-CPC cooperation was accelerated. CPC organizations at all levels mobilized their members and young people to join the KMT and actively promoted the National Revolutionary Movement nationwide. In early October 1923, at the invitation of Sun Yat-sen, Soviet representative Mikhail Borodin arrived in Guangzhou. Sun Yat-sen appointed Borodin to the KMT’s organizational instructor post, and later the position of political advisor. The reorganization of the KMT soon entered the implementation phase.

The First National Congress of the Chinese KMT was held in Guangzhou in January 1924. Among the 165 delegates at the opening ceremony, more than 20 were CPC members. Li Dazhao was appointed to the presidium of the Congress by Sun Yat-sen.

The Congress adopted the Declaration of the First National Congress of the Chinese Kuomingtang. The document contained a new interpretation of the Three Principles of the People, which were rechristened the New Three Principles of the People. “Nationalism” now referred to anti-imperialism; “Democracy” stressed the democratic rights shared by all ordinary people; and “People’s Livelihood” incorporated the major principles of “equalizing land rights” and the “regulation of private capital.”

Shortly after the Congress, Sun Yat-sen also put forward the slogan “Land to the tiller.” The political program of the Congress was consistent with certain basic principles of the CPC’s political program for democratic revolution, and as such, it became the political basis for the first instance of KMT-CPC cooperation. The Congress confirmed the principle that CPC members should join the KMT on an individual basis.

The Congress elected the Central Executive Committee of the KMT. Ten Communists, including Li Dazhao, Tan Pingshan, and Mao Zedong, were elected as members or alternate members of the Central Executive Committee, accounting for about a quarter of the total. After the Congress, CPC members with important posts in KMT headquarters included: Tang Pingshan, director of the Department of Organization; Lin Boqu, director of the Department of Peasantry; and Mao Zedong, acting director of the Department of Publicity.

The Congress also established the Three Great Policies—alliance with Russia, cooperation with the CPC, and assistance for peasants and workers, marking the start of the first instance of KMT-CPC cooperation.

A New Revolutionary Landscape and the Fourth National Congress of the CPC

Soon after KMT-CPC cooperation began, the revolutionary forces of the country, centered on Guangzhou, opened a new phase of revolution against imperialism and feudal warlords.

KMT-CPC cooperation helped restore and develop the workers’ movement. In July 1924, in the Shamian Concessions in Guangzhou, several thousand workers staged a political strike to protest against a new police regulation, issued by the British and French authorities, denying Chinese citizens free access to the concessions. Chinese police also participated in the strike, which lasted for over a month and ended in victory. In May of the following year, the All-China Federation of Trade Unions was founded at the Second National Labor Congress in Guangzhou.

The peasant movement was also developing steadily. Peasants in various counties of Guangdong launched peasant associations and organized self-defense armies to fight local tyrants, evil gentry, and corrupt officials. Beginning from July 1924, six sessions of the Peasant Movement Institute were held in Guangzhou, presided over by Communists Peng Pai and Mao Zedong. The institute helped train a number of leading activists for the peasants movement. In addition, the student movement and the women’s movement also grew.

In order to foster a backbone force for armed revolution, the KMT decided at its First National Congress, at the suggestion of the Communists, to establish an army officer school—the Whampoa Military Academy. The CPC sent a large number of its members, members of the Socialist Youth League, and revolutionary youths from all over the country to study at the academy. There were 56 CPC and Socialist Youth League members among the academy’s first group of enrollees, representing one tenth of the total.

Thanks to the joint efforts of the KMT and CPC, the ideas of the National Revolution spread across the country from south to north on an unprecedented scale. In October 1924, General Feng Yuxiang of the Zhili clique of the Northern Warlords staged a coup and overthrew the Beijing government, which was controlled by the warlords Cao Kun and Wu Peifu. After taking over Beijing and Tianjin and reorganizing his army into the National Army, Feng sent a telegram to Sun Yat-sen inviting him to come north to “discuss state affairs.” In November, Sun Yat-sen left Guangzhou to travel north. He promoted the idea of holding a national assembly and abolishing unequal treaties along the way. People’s organizations from all over the country sent him telegrams expressing their support for him. The trip grew into a broad-based publicity campaign.

In order to strengthen the leadership of the growing revolutionary movement, the CPC held its Fourth National Congress in Shanghai in January 1925. The Congress was attended by 20 delegates, representing 994 CPC members in the country.

The great historical achievement of the Fourth National Congress was that it discussed the leadership of the proletariat in the democratic revolution and called for an alliance of workers and peasants. It enriched the content of the democratic revolution, pointing out that while opposing international imperialism, it was necessary to also oppose feudal warlord politics and feudal economic relations. This showed that the CPC’s understanding of Chinese revolution had greatly improved, based on its review of the practical experience gained since its founding, particularly during the previous year of KMT-CPC cooperation.

The Congress also decided to strength CPC organizations throughout the country, expanding its numbers and consolidating discipline. It specified branches as the basic organizations of the CPC.

The Congress revised the section of the Party Constitution dealing with Party branches to stipulate that Party branches may be organized wherever there are three or more Party members.

The Congress elected the Central Executive Committee, which in turn elected the Central Bureau with Chen Duxiu as the general secretary.

On March 12, 1925, Sun Yat-sen passed away in Beijing. Following Sun’s death, the anti-communist right-wingers of the KMT sprang back into action, resulting in a deeper split between the left and right wings of the KMT. The united front based on KMT-CPC cooperation was now facing a much more complex situation. This proved to be a great trial for Chinese Communists.

The May 30th Movement and the Unification of the Guangdong Revolutionary Bases

The nationwide Great Revolution culminated in a workers’ strike against foreign capitalists in Shanghai in May 1925.

On May 15, 1925, a Japanese capitalist at the Naigai No.7 Cotton Mill shot dead Gu Zhenghong, a worker and CPC member. On May 30, workers and students took to the streets in Shanghai under the leadership of the CPC. British constables in the Concession suddenly opened fire on Nanjing Road, killing 13 people, students and workers among them, and injuring countless others. This atrocity, which became known as the May 30th Massacre, shocked the entire country. Over the next few days, another series of incidents occurred in Shanghai and other places where British and Japanese soldiers and police fired on common people.

The May 30th Massacre enraged people all over China. Fury over imperialism, which had for many years built among the Chinese people, suddenly erupted, sparking strikes by workers, students, and merchants. The CPC Central Executive Committee established the Shanghai Federation of Trade Unions, and at the same time set up the Shanghai United Committee of Workers, Merchants, and Students to provide stronger leadership for the movement, which drew about 17 million people from all over the country. Roars of “Down with imperialism” and “Abolish unequal treaties” rang out all across the country, from bustling cities to remote towns. The massacre triggered a national wave against imperialism that surged across the nation with unstoppable momentum. This is remembered in history as the May 30th Movement.

The Guangzhou-Hong Kong Strike, involving 250,000 people, was an important component of the May 30th Movement. Striking workers established the Guangzhou-Hong Kong Strike Committee, with CPC member Su Zhaozheng as chairman, and imposed a blockade on Hong Kong. The strike lasted for 16 months. The over 100,000 organized strikers who had gathered in Guangzhou became a strong pillar of the Guangzhou Revolutionary Government.

The CPC grew considerably during its leadership of the May 30th Movement. It expanded from less than 1,000 members at the beginning of the year to 10,000 at the end. New CPC organizations were established in many places in the country. To adapt to the new situation arising from the climax of the Great Revolution, the CPC Central Executive Committee promptly put forward the idea of “transforming itself from a small organization to a centralized mass party” in a very short time. It also stressed the importance of education and training for CPC members and set up an advanced CPC school in Beijing to train cadres.

Under the favorable conditions, the KMT and the CPC worked together to unify the revolutionary bases in Guangdong. In 1925, after two eastern expeditions and a southern expedition, the troops of the warlord Chen Jiongming and the troops of the warlord Deng Benyin were eliminated; a rebellion staged by the troops under the command of Yang Ximin and Liu Zhenhuan in Guangzhou was quelled. These actions unified the Guangdong revolutionary bases and created a far more reliable rear base from which to launch the Northern Expedition.

In addition, the CPC also made an attempt to create armed forces directly. Sun Yat-sen gave his support to Zhou Enlai and the Guangdong Regional Committee of the CPC to reorganize the armored corps of the headquarters of the Army and Navy Grand Marshal’s Office into a revolutionary armed force under direct CPC leadership, with members of the CPC and Communist Youth League as its mainstay. In early 1926, an independent regiment was established within the Fourth Army of the National Red Army (NRA) under the command of CPC member Ye Ting.

The revolutionary movement in the North prospered due to the hard work of Li Dazhao and other Communists. At the beginning of 1924, the northern workers’ movement gradually rose out of the despondency which ruled in the aftermath of the February 7th Massacre to recover and gain momentum. Workers held many strikes in Beijing, Qingdao, and Tangshan. In October 1925, at an enlarged meeting, the CPC Central Executive Committee stressed the importance of work in the North and decided to strengthen leadership over the revolution there. After the meeting, the CPC Northern Executive Committee was established with Li Dazhao as secretary.

By July 1926, more than ten local committees and dozens of special and independent branches had been created in Beijing, Tianjin, Tangshan, Taiyuan, and Northern Manchuria, with more than 2,000 CPC members. Li Dazhao and the Party organizations in the North also worked to win over Feng Yuxiang and his National Army, and launched a movement for tariff autonomy. These struggles demonstrated an awakening of the revolutionary consciousness of the people of the North and dealt a blow to the reactionary government of Duan Qirui who controlled Beijing.

(See first post for background: #1 Cultural Revolution, previous post: #3 May 4th Movement and Spread of Marxism in China)

A Concise History of the Communist Party of China (2021, ISBN 978-7-5117-3978-0), pg. 13-22

《中国共产党简史》, pg. 11-19

(Chapter 1)

3. The Founding of the CPC and the Creation of the Platform of Democratic Revolution

The Establishment of Early Communist Party Organizations and Their Activities

With the dissemination of Marxism in China and the emergence of progressives who embraced its ideas, the conditions were ripe in terms of ideology and personnel for founding the Communist Party of China. The task of establishing a working-class political party was put on the agenda.

The idea of establishing a communist party in China was first mooted by Chen Duxiu and Li Dazhao. They realized that to transform China using Marxism it would be necessary to establish a proletarian party to take charge of the revolution. To avoid persecution from the reactionary warlord government, Chen Duxiu moved secretly from Beijing to Shanghai in February 1920. He was escorted on his trip by Li Dazhao, during which the two discussed the establishment of communist party organizations in China.

In March 1920, Li Dazhao established the Society for Marxist Studies at Peking University, which was not only the first group to study and research Marxism in China but also an important preparatory organization for the founding of the Communist Party of China. In April, the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) sent a plenipotentiary Grigory N. Voytinsky to China, along with others. The group met Li Dazhao in Beijing and Chen Duxiu in Shanghai to discuss the establishment of a communist party in China. These discussions materially contributed to the CPC’s creation.

The first early communist party organization was established in Shanghai, a core city with the greatest concentration of workers in China. In May 1920, Chen Duxiu founded the Society for the Study of Marxism to discuss the doctrine of socialism and the transformation of Chinese society. That August, an early communist party organization was set up in the editorial office of New Youth in Shanghai, with Chen Duxiu as secretary. In November, the Communist Party organization drew up the “Manifesto of the Communist Party of China,” which stated that “the aim of the Communists is to create a society in accordance with the communist ideal.” This early organization proved to be an initiator of the CPC and served as a key liaison point for Chinese Communists in various places.

In October 1920, another communist party organization was founded in Beijing by Li Dazhao and others, which was known as “Communist Party Group” at the time. At the end of the year, the decision was made to set up a Beijing branch of the communist party with Li Dazhao as secretary.

The early organizations of the CPC in Shanghai and Beijing actively worked to lend impetus to the founding of CPC organizations in other parts of the country. From the autumn of 1920 to the spring of 1921, with the support of the first two organizations in Shanghai and Beijing, communist party organizations were formed in Wuhan by Dong Biwu, Chen Tanqiu, and Bao Huiseng, in Changsha by Mao Zedong and He Shuheng, in Jinan by Wang Jinmei and Deng Enming, and in Guangzhou by Tan Pingshan and Tan Zhitang. In Japan and France, communist party organizations composed of Chinese students and progressive overseas Chinese were also established.

After their founding, these early communist party organizations primarily carried out the following activities: studied and promoted Marxism and examined China’s practical problems; denounced anti-Marxist ideas and enabled a host of progressives to turn to Marxism by helping them draw a clear line between socialism and capitalism and scientific socialism and other forms of socialism; carried out publicity and organizational work among workers, enabling them to receive Marxist education and raise their class consciousness; and established Socialist Youth League organizations which organized the study of Marxism for their members and arranged for them to take part in concrete struggles, thus cultivating reserve forces for a communist party.

The Communist Manifesto played an important role in the theoretical preparations for the founding of the CPC. In February 1920, to translate The Communist Manifesto, Chen Wangdao secretly returned to his home in Yiwu County, Zhejiang Province. So devoted was he to his mission that he once dipped a sticky rice dumpling into his ink bowl instead of brown syrup. Oblivious to his mistake, Chen declared the snack to be “sweet enough.” The truth is indeed extremely sweet. This was a vivid example of the thirst among Chinese Communists for the truth of Marxism and their firm belief in the ideals of communism. The Chinese translation of The Communist Manifesto, which was published in August 1920, was a major event in the history of the dissemination of Marxism in China.

The CPC’s First National Congress

In July 1921, the First National Congress of the CPC opened at 106 Wangzhi Road (now 76 Xingye Road) in the French Concession of Shanghai.[1]

The delegates in attendance at the meeting were Li Da and Li Hanjun from Shanghai, Zhang Guotao and Liu Renjing from Beijing, Mao Zedong and He Shuheng from Changsha, Dong Biwu and Chen Tanqiu from Wuhan, Wang Jinmei and Deng Enming from Jinan, Chen Gongbo from Guangzhou and Zhou Fohai from Japan; and Bao Huiseng (sent by Chen Duxiu).[2] They represented more than 50 CPC members across the country. Henk Sneevliet (alias Maring) and V. A. Nikolsky attended as representatives of the Communist International. Chen Duxiu and Li Dazhao did not attend the Congress due to their busy schedules.

To escape the attention of spies and the searches mounted by the French Concession police, the final session of the congress was held on a pleasure boat on South Lake in Jiaxing, Zhejiang Province.

The First National Congress decided that the name of the new party would be “the Communist Party of China” and adopted its first program. The program consisted of the following points: The revolutionary army shall join hands with the proletariat in overthrowing the bourgeois regime; and the Party shall accept the dictatorship of the proletariat until the end of class struggle, abolish capitalist private ownership, and align itself with the Third International. The CPC made socialism and communism its goals and revolution the means for achieving them as soon as it was established.

The First National Congress decided to set up the Central Bureau as a temporary leading body for the CPC’s central leadership. The Congress elected the Central Bureau with Chen Duxiu as its secretary.

The First National Congress formally declared the founding of the CPC. The CPC’s founding was an inevitable product of the historical development of modern China, of the Chinese people’s tenacious struggle for survival, and of the journey toward the rejuvenation of the Chinese nation. As the party of the most advanced class in China—the working class, the CPC represents not only the interests of the working class, but also those of the Chinese people and the Chinese nation as a whole. From the beginning, it followed Marxist theory as its guide for action, and it made it its mission to work for the happiness of the Chinese people and the rejuvenation of the Chinese nation.

The founding of the CPC was a groundbreaking event in the history of the Chinese nation, with tremendous, far-reaching significance. The most important reason for the repeated setbacks and failures of the Chinese people in their struggle against imperialism and feudalism in modern times was the absence of a strong and advanced political party to act as a leading core with the power to unify. The birth of the CPC fundamentally changed this situation.

Both sites of the First National Congress, in Shanghai and on the Red Boat on Lake Nanhu in Jiaxing, are the birthplaces of the CPC, the places from where the Party’s dream set sail. The very act of founding the CPC was a demonstration of the Party’s pioneering spirit, indomitability, and devotion to the public good and the people’s interests. These qualities, which underpin the revolutionary spirit of China, are also important elements of the Party’s “Red Boat spirit.” It was by only adhering to this spirit and carrying it forward that the CPC could create miracle upon miracle, that it could build a new society, became the world’s largest political party, and bring profound change to China and have a profound impact on the world.

The CPC’s Second National Congress and the Formulation of the Platform of the Democratic Revolution

After the founding of the CPC, the Party’s most important task was to apply scientific theories to observe and analyze China’s actual conditions. At the time, the most prominent problem in China was the conflict between China’s warlords, which was growing in ferocity under the manipulation of the imperialists. The Party was deeply aware that given the volatile situation, it would have no chance of realizing its ideals if it could not overthrow the regimes of the warlords and imperialists.

The Second National Congress of the CPC was held in Shanghai in July 1922. The Congress was attended by 12 delegates, representing 195 CPC members nationwide.

Through an analysis of China’s economic and political situation, the Congress revealed the semi-colonial and semi-feudal nature of Chinese society and pointed out that the maximum program of the CPC was to realize socialism and communism, while the minimum program in the present stage was to defeat the warlords, overthrow the oppression of international imperialism, and unify China into a genuine democratic republic. The Congress pointed out that in order to achieve its anti-imperialist and anti-warlord revolutionary goal, a “democratic united front” must be formed with all revolutionary parties and bourgeois democrats in the country.

Just a year after its founding, the CPC proposed an explicit anti-imperialist and anti-feudalist program of democratic revolution, the first of its kind in China. The Party ensured that this program was very quickly spread far and wide. As calls of “down with the imperialist powers; down with the warlords” became the common cry among the people, it became clear that only the CPC, armed with Marxism, could point the way forward for the Chinese revolution.

The Second Congress adopted the CPC’s first Constitution, which contained specific provisions on the conditions for membership, the CPC’s organizations at all levels, and its discipline, all explicitly based on the principle of democratic centralism. This was of great importance for strengthening the Party. The Congress adopted a resolution confirming that the CPC was a branch of the Communist International.

The Congress also adopted a resolution stating that the CPC was a party composed of the most revolutionary elements of the proletariat, and that it was “a party struggling for the proletarians.” It stressed that all of its campaigns must reach out to the people and must never alienate them. This resolution proved to be highly significant in initiating the worker and peasant movements in the early days of the CPC.

The Second CPC National Congress elected the Central Executive Committee with Chen Duxiu selected as committee chairman.

The First Upsurge of the Workers’ Movement and the Initial Development of the Peasant Movement

After its founding, the CPC strove to organize and lead the workers’ movement, establishing the Secretariat of the Chinese Labor Organization in August 1921 as a headquarters for openly leading the movement. The Secretariat published the Labor Weekly, organized workers’ schools and industrial unions, and launched strikes. This increased the CPC’s influence among workers and across society generally.

Under CPC’s leadership, the first upsurge of the Chinese workers’ movement began with the Hong Kong Seamen’s Strike in January 1922 and ended with the Beijing-Hankou Railway strike in February 1923. Over these 13 months, China was swept by more than 100 strikes, involving over 300,000 people. The railway workers and coal miners’ strike in Anyuan and coal miners’ strike in Kailuan were hallmarks of this upsurge, fully demonstrating the power of the working class when well-organized.

There were more than 17,000 workers at the Anyuan mine and railway. During the autumn and winter of 1921, Mao Zedong, then the Party branch secretary of Hunan Province, visited Anyuan on a fact-finding mission. Li Lisan travelled to Anyuan after this to organize the workers there. On May 1, International Labor Day, 1922, a trade union, the Anyuan Mine and Railway Workers’ Club, was established. In early September, Mao Zedong returned to Anyuan to organize a strike. He was followed by Liu Shaoqi. The strike began on September 14, with workers demanding protection for their political rights, wage increases, and other conditions. Thanks to the valiant struggle of the workers and the sympathy and support they won from people of all walks of life, the mine and railway authorities were forced to meet most of their demands, bringing the Anyuan strike to a victorious conclusion.

On February 4, 1923, workers of the Jinghan (Beijing-Hankou) Railway went on strike to fight for the establishment of the Jinghan Railway Trade Union. On February 7, backed by imperialist forces, the warlord Wu Peifu deployed soldiers and police officers to violently suppress the strike. Reactionaries tied Lin Xiangqian, president of the Jiang’an Branch of the Union in Hankou (a Communist Party member), to a pole and tried to force him to call the strikers back to work. Refusing to surrender, Lin died a hero’s death. Shi Yang, a union legal advisor (also a Communist Party member), was also killed. Having been struck by three bullets, he shouted “Long live the workers!” three times before he died. In the February 7th Massacre, 52 people lost their lives, more than 300 were injured, more than 40 were arrested and imprisoned, while more than 1,000 people were dismissed from their jobs and forced into exile. After the incident, the national workers’ movement fell to a nadir.

While leading the revolutionary struggle, the CPC began, too, to strengthen itself. It started to establish primary-level organizations in industrial and mining enterprises. It also welcomed into its ranks a number of outstanding figures who had emerged as the workers’ struggle unfolded, including Su Zhaozheng, Shi Wenbin, Xiang Ying, Deng Pei, and Wang Hebo.

In addition to focusing on the workers’ movement, the CPC also initiated peasant movements in the countryside. In September 1921, a peasants’ meeting was held in Yaqian Village, Xiaoshan County, Zhejiang Province, at which the first of a new kind of peasants’ organization was founded. In July 1922, Peng Pai established the first secret peasant association in his hometown of Haifeng County, Guangdong Province. By May 1923, peasant associations had been established in Haifeng, Lufeng, and Huiyang counties, and had a combined membership of more than 200,000. In September of the same year, inspired by the workers’ movement in Shuikoushan, peasants in Baiguo of Hengshan Couny, Hunan Province, established the Yuebei Peasants and Workers Association under CPC leadership. It launched a series of struggles and raised the first flag of the peasant movement in Hunan Province. In addition, the CPC also led the youth and women’s movements.

Both the worker and peasant movements, which had been launched and organized under CPC leadership, but particularly the workers’ movement, demonstrated the firm revolutionary commitment and great fighting capacity of the Chinese working class. As a result, the CPC expanded its influence throughout the country, allowing for its cooperation with other revolutionary forces in launching a great nationwide revolution.

[1] It was verified many years later that the exact date of the CPC’s First National Congress was July 23, 1921. In June 1941, the CPC Central Committee issued the Instruction of the Central Committee on the 20th Anniversary of the Founding of the CPC and the 4th Anniversary of the War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression, officially recognizing July 1 as the founding date of the CPC. From then on, July 1 was fixed as the anniversary of the CPC’s founding.

[2] Zhang Guotao surrendered to the Kuomingtang in 1938 and was expelled from the CPC. Chen Gongbo and Zhou Fohai seriously violated Party discipline and were expelled from the Party shortly after the First National Party Congress. They turned traitors during the War of Resistance against Japan.

This time we're reading chapter 8 of Capital Volume 1. Participation welcome at any time, not just on the weekend of week 16, either in this thread or in our Matrix room (see this post for instructions on how to join)

(See first post for background: #1 Cultural Revolution, previous post: #2 China before the CPC)

A Concise History of the Communist Party of China (2021, ISBN 978-7-5117-3978-0), pg. 5-13

《中国共产党简史》, pg. 4-11

(Chapter 1)

2. The May 4th Movement and the Spread of Marxism in China

The New Culture Movement and the Influence of the Russian October Revolution on China

The founding of the Republic of China did not bring the national independence, democracy, and social progress that people longed for. Hope was thus supplanted by profound despair. Since they found the old road impassable, people began to look for new ways out of their plight. Some progressive intellectuals began by reviewing the lessons of the Revolution of 1911. They determined to launch a new enlightenment movement, one that would eliminate obscurantism, awaken the nation, and free people’s minds from the shackles of feudalism. Known as the New Culture Movement, this campaign became a harbinger for great social change.

The New Culture Movement was born in Shanghai in September 1915 with the launch of Youth Magazine (later renamed New Youth) by Chen Duxiu. In 1917, Chen became the Dean of Liberal Arts at Peking University, and the editorial office of New Youth was moved to Beijing. The New Culture Movement was thus based around Peking University and the New Youth publication.

The movement made “Mr. Democracy” and “Mr. Science” its icons. Advocates used evolutionary theory and the emancipation of personality as their main weapons to violently attack Confucius and other “sages of the past.” They advocated a new morality and new literature and railed against those of the past. They promoted a vernacular writing style over the classical style. By criticizing Confucianism, they shook the dominance of feudal orthodoxy, opened the gates to new ideas, and generated a surge of ideological revolution in Chinese society.

The New Culture Movement still took bourgeois democracy as the plan for saving the nation. However, the inherent problems of the capitalist system were already evident in Europe and America, the birthplace of those ideas. World War I had served to only magnify these insurmountable problems in a most extreme way. The repeated failures of Chinese attempts to learn from the West led Chinese progressives to question the feasibility of a bourgeois republic on Chinese soil. Yet again, Chinese progressives’ explorations of plans for saving the nation reached an important historical crossroads.

It was at this point, in 1917, that the salvoes of the October Revolution brought to China the ideas of Marxism-Leninism. In the scientific truth of Marxism-Leninism, Chinese progressives saw a solution to China’s problems. The October Revolution was also a call to resist imperialism, a painful, solemn, and deeply meaningful cry in the ears of the Chinese people, who had for so long been tyrannized by imperialist powers. This prompted Chinese progressives to lean toward socialism and inspired them to gain a serious understanding of Marxism, the guide of the October Revolution. As a result, a group of intellectuals with incipient communist ideas emerged in China in support of the Russian October Revolution.

Li Dazhao was the first in China to embrace the October Revolution and one of the first to disseminate Marxism in China. Beginning in July 1918, he published articles arguing that the October Revolution was the forerunner of a 20th century world revolution and a new dawn for all humankind. His articles included “A Comparison of the French and Russian Revolutions,” “The Victory of the Common People,” and “The Victory of Bolshevism,” which enthusiastically praised the victory of the October Revolution. Li predicted that an irresistible tide had been set in motion by the October Revolution and that the future would surely see “a world of red flags.” After the May 4th Movement, he worked even harder to promote Marxism, and published the article “My View on Marxism.” This piece provided a systematic introduction to Marxist theory and had widespread influence among intellectual circles. This was a sign of the systematic way in which Marxism was now being disseminated in China. Li Dazhao also wrote other articles, including “More on Problems and Doctrines,” in which he criticized anti-Marxist ideas and argued that Marxism was suited to China’s needs.

Why did the October Revolution that erupted in Russia in 1917 call forth such response in China? In large part, it was down to the changes that were sweeping Chinese society. While radical changes were taking place in the thinking of Chinese intellectuals, profound shifts were also quietly occurring in China’s social structure. The country’s national capitalist economy had developed rapidly during World War I, as the Western imperialist countries, busy fighting at close quarters on the European battlefield, temporarily slackened their economic aggression against China. This saw the Chinese working class and national bourgeoisie grow in strength. On the eve of the May 4th Movement of 1919, industrial workers numbered about two million and were becoming an increasingly important force in society.

China’s working class is a great revolutionary class born in modern China. In addition to its basic qualities—its association with the most advanced form of economy, its strong sense of organization and discipline and its lack of private means of production—the Chinese proletariat has many other outstanding qualities. For example, it was more resolute and thorough in revolutionary struggle. Under the historical conditions of China as a semi-colonial and semi-feudal society, the Chinese proletariat was the fundamental driving force behind the Chinese revolution. Meanwhile, there was a rapid increase in the number of students enrolled in various new types of schools, and a great many teachers also emerged from such centers of learning, along with many journalists, thereby helping to create a larger contingent of intellectuals than there had been in the period of the Revolution of 1911. This cohort was also in possession of more advanced ideas. These factors made the rise of a great new people’s revolution inevitable.

The May 4th Movement: The Dawn of the New-Democratic Revolution

The immediate trigger for the May 4th Movement was China’s diplomatic failure at the Paris Peace Conference.

In the first half of 1919, the victorious Allied Powers of World War I held a “peace conference” in Paris. At the conference, the Chinese delegation put forward seven proposals (including the abolishment of foreign spheres of influence in China and the withdrawal of foreign troops from the country) and called for the cancellation of the Twenty-One Demands[1] and the related notes exchanged between China and Japan. The Conference rejected China’s just requests and stipulated that Germany should transfer concessions in Shandong Province to Japan. The Northern Warlord government, capitulating under imperialist pressure, was prepared to sign such a peace treaty. When the news reached China, it sparked outrage among people from all walks of life. On May 4, more than 3,000 students in Beijing gathered in front of Tian’anmen Square to demonstrate. The protesters shouted slogans such as “Defend Chinese sovereignty against external aggressors and get rid of internal traitors,” “Annul the Twenty-One Demands,” “Return Qingdao to China,” and “Punish the traitors Cao Rulin, Zhang Zongxiang, and Lu Zongyu.”[2] Breaking through multiple barriers erected by reactionary military police, the crowd assembled in front of Tian’anmen Gate. The May 4th Movement, which stunned people in China and around the world, had erupted.

During the movement, the Chinese working class also entered the political arena as an independent force. From June 5 onwards, workers in Shanghai went on strike in solidarity with students, and within a few days, the number of striking workers reached 60,000 to 70,000. Strikes followed in Beijing, Tangshan, Hankou, Nanjing, and Changsha, and merchants in many large and medium-sized cities also staged strikes. As strikes were ongoing in three different arenas—workplaces, schools, and markets, the May 4th Movement reached a climax. The struggle swept across the country, engulfing over 100 cities in more than 20 provinces.

Although initiated by intelligentsia, the May 4th Movement evolved into a nationwide mass movement with the participation of the working class, petty bourgeoisie, and bourgeoisie. As a result of public pressure, the Northern Warlord government released the students it had taken into custody, and announced the dismissal of Cao Rulin, Zhang Zongxiang, and Lu Zongyu. On June 28, the Chinese delegates refused to sign the Paris Peace Treaty.

The May 4th Movement was an epoch-making event in the history of modern Chinese revolution, in that it signaled the dawn of a new-democratic revolution. With a revolutionary nature in diametrical opposition to imperialism and feudalism, a progressivesness that sought the truth for saving the country and making it strong, and broad-based participation from people of all ethnic groups and walks of life, the May 4th Movement promoted progress in Chinese society, the extensive circulation of Marxist ideas around China, and the integration of Marxism with the Chinese workers’ movement. It helped develop the ideology and the cadres for the founding of the CPC. Out of the Movement grew the great May 4th spirit, which features patriotism, progress, democracy, and science as its main inspirations with patriotism at its core. This movement was a milestone in the history of the Chinese nation’s quest for independence, development, and progress in modern times.

The Spread of Marxism in China

In the period before and after the May 4th Movement, the practical lessons of the Paris Peace Conference made Chinese progressives see that the imperialist powers were working together to oppress the Chinese people. This contributed directly to the further spread of socialist ideas in China. In March and April 1920, The East and other periodicals published the first declaration of the Soviet Russian government to China, in which it announced that all privileges (enjoyed by czarist Russia in China) would be abolished, thus creating further impetus for the spread of socialist ideas in China. The study and promotion of socialism gradually became the norm among the progressive intelligentsia.

Under these circumstances, many progressive intellectuals from different backgrounds came to Marxism by different routes, having carefully considered the alternatives.

Li Dazhao played a major role in the early stage of the Marxist movement in China. He edited no.5, vol.VI of New Youth, a special issue devoted to Marxism in 1919. He also helped to start a new column, “the Study of Marx,” in the Beijing-based Chen Pao.

Chen Duxiu, one of the intellectual leaders of the New Culture Movement, also turned to Marxism. He warned that China should not take the path followed by Europe, the United States, and Japan after the May 4th Movement. Chen declared it necessary to establish a state of the laboring classes by means of revolution.

Mao Zedong enthusiastically praised the victory of the October Revolution in the Xiangjiang Review, of which he was the editor-in-chief, declaring that it would spread worldwide and that the Chinese should follow its example. After he came to Beijing for the second time, he eagerly sought out and studied communist works, helping establish his faith in Marxism. Many years later he called, “By the summer of 1920 I had become, in theory and to some extent in action, a Marxist.”

Some veteran members of the Tong Meng Hui (Chinese Revolutionary League) also began to turn to proletarian socialism. Many years later, Dong Biwu recalled how he and others had joined Sun Yat-sen in the revolution. “The revolution forged ahead, but Sun Yat-sen failed to get hold of it and, as a result, it was snatched by others. We therefore began to study the Russian pattern.”

Guided by Marxism, Chinese progressives devoted themselves to the practice of mass struggle. At the beginning of 1920, some revolutionary intellectuals in Beijing visited the residential areas of rickshaw workers to investigate their desperate living conditions. Deng Zhongxia and others went to Changxindian to tell workers about the revolution and establish contacts with them. In this way, the advanced intellectuals helped connect Marxism with the Chinese workers’ movement.

[1] The Twenty-One Demands were set forth in 1915 by Japan whose purpose was to destroy China. Some of these unreasonable demands were designed to confirm Japan’s dominant position in Shandong, the southern part of the three provinces of the Northeast, and eastern Inner Mongolia.

[2] The three pro-Japanese bureaucrats in the Northern Warlord government.

A very educational thread addressing this article headline:

"US treasury secretary is in China to talk trade, anti-money laundering and Chinese 'overproduction'"

Here the text in case the link doesn't work for you or stops working at some point:

The goal of this pressure campaign is to somehow convince China to self-sabotage the foundation of their budding prosperity—their means of production—thereby eliminating the competition.

Why don't the capitalist countries try to out-compete China on commodity prices instead?

They've tried!

But due to decades of offshoring productive capacity and hoovering up their best and brightest minds into the financial and "tech" sectors, regaining a competitive edge will require a lot more effort than simply throwing money at the problem.

In the lead up to Yellen's visit, western pundits have begun calling for China to reorient its fiscal policy away from direct subsidy of domestic industry and toward a western model of social welfare spending and imports; essentially, to treat symptoms instead of the disease!

The disease is, of course, capitalism itself. And at the core of the capitalist mode is commodity production.

Since China's economy is undoubtedly still dominated by commodity production, it is easy to see this as de facto proof that China's model is not socialist.

But history has shown that commodity production is a historical stage that must be progressed through, not simply a policy that can be abolished by decree.

So how is China progressing from this ‘lower’ stage of socialism toward a ‘higher’ stage?

By undercutting imperialism, the core of global capital's political power.

The beating heart of imperialism is monopoly-like control of the global economy, which is why China’s sovereign command of critical global commodities poses an existential threat to the imperialist order.

In response, the US is crying out “slave labor!” in unison across virtually every sector; from clothing, to vehicles, to phones.

In reality, China’s commodities aren’t cheap because of a surplus of labor, but because of a ‘lack’ of it!

As anyone with experience manufacturing in China during the past two decades can attest, plummeting commodity prices are due to a rapidly surging level of automation.

This increasing automation leads to a decrease in the embodied labor within each commodity.

In capitalist countries, the decline in embodied labor erodes the whole basis for profit, and is thereby a major cause of the pattern of recurring market crashes and economic crises.

But in China, "overproduction" isn’t ultimately measured against the market’s demand for profit, but by societal need.

China’s recent reigning-in of their housing “glut” (without a single person being made homeless) was a great demonstration of this principle in action.

The only reason China (or any socialist country) is able to make steady progress toward resolving the set of shifting contradictions they face is because the political power of capital has been subordinated to the political power of the party, the vanguard of the working class.

But in truth, there is no set formula for developing a ‘modern socialist country with common prosperity’.

Marx provided only a strategy of navigation, not a roadmap.

China must navigate themselves and “cross the river by feeling the stones”.

One of the stones that has consistently guided China is 'hard work', a value that is integral to China's national identity.

And with the amount of industrial catching-up the west has to do, it will eventually need to become part of ours as well.

(See previous post for background: #1 Cultural Revolution)

A Concise History of the Communist Party of China (2021, ISBN 978-7-5117-3978-0), pg. 1-5

《中国共产党简史》, pg. 1-4

Chapter I

The Founding of the Communist Party of China and Its Involvement in the Great Revolution

One night in July of 1921, the First National Congress of the Communist Party of China (CPC) opened in secret in a small two-story residence in Shanghai’s French Concession. This moment gave birth to a completely new party of the proletariat whose actions were to be guided by Marxism and Leninism. This was a truly groundbreaking event—a momentous occasion which, like a torch held aloft in the darkness, brought light and hope to the deeply distressed Chinese people. From that moment on, the Chinese people have had in the Party an anchor for their struggles to achieve national independence and liberation, to make their country prosperous and strong, and to realize happiness and contentment, and their mindset changed from passivity to taking the initiative.

1. Various Forces Explore Ways to Rejuvenate China in Modern Times

Over the course of several millennia, the Chinese people created an enduring and splendid civilization, making a marvelous contribution to humankind and becoming one of the great peoples of the world. Following the advent of modern times, however, owing to the aggression of Western powers and the corruption of China’s feudal rulers, China was gradually reduced to a semi-colonial and semi-feudal society. As the land of China was laid to waste and the people descended into misery, the Chinese nation experienced suffering of unprecedented proportions.

From 1840 onwards, Western powers launched numerous wars of aggression against China (most famous are the Opium War of 1840–1842 involving Great Britain, the Second Opium War of 1856–1860 with Great Britain and France, the Sino-French War of 1884–1885, the Sino-Japanese War of 1894–1895, and the war of 1900 against the aggression of the Eight-Power Allied Forces). Through these wars and other methods, Western powers forced China to cede territory and pay out indemnities, and they greedily extracted privileges of all kinds from China. Britain carved away Hong Kong, Japan occupied Taiwan, and czarist Russia seized the northeastern and northwestern parts of the country. Over one billion taels of silver were extracted from China in war indemnities, even though the Qing government generated just over 80 million taels of annual revenue at the time.

Through unequal treaties of increasingly harsher terms, Western powers obtained many important privileges in China, such as the right to set up ports and concessions, open mines and factories build railways, establish banks and businesses, build churches, station troops, demarcate spheres of influence, and enjoy consular jurisdiction and unilateral most-favored-nation treatment. Hundreds of unequal treaties and conventions, like an all-encompassing net, entrapped China politically, economically, militarily, and culturally. As a result, it was utterly helpless in the face of endless demands, and while it encountered reproach at every turn, Western powers had their way in the country on the strength of their treaties. They ran China’s trading ports, customs, foreign trade, and transport lines and dumped large quantities of their goods in China, treating it as a market for their products and a base for extracting raw materials.

The old summer palace, Yuanmingyuan, was razed to the ground by British and French troops; the Beiyang Fleet was completely annihilated in the Sino-Japanese War of 1894–1895; and the forces of the eight imperialist powers—Britain, the United States, Germany, Japan, Russia, France, Italy and Austria burned, killed, raped and looted its way through Beijing in 1901. Such atrocities became indelibly etched in the memory of the Chinese nation. More and more, the Qing government, representing the interests of China’s landlord class and comprador bourgeoisie, became little more than a tool for foreign capitalist rule of China, a traitorous and corrupt regime strangling all vitality from the country. The conflicts between imperialism and the Chinese nation, and between feudalism and the people, thus became the principal conflicts of modern Chinese society. As the Chinese people were reduced to extreme misery, the prospect of imminent destruction loomed for the Chinese nation.

It was at this point that national rejuvenation became the greatest dream of the Chinese people in modern times, and the quest to achieve national independence and liberation, to make the country prosperous and strong, and to realize happiness and contentment became the historic tasks of the Chinese people. The Chinese nation enjoys a glorious tradition of constant self-improvement, and it would never halt the struggle to defend its independence, dignity, and civilization. Many brave men and women stepped forward and devoted their lives to the cause of national progress prior to the founding of the Communist Party of China, working unceasingly to alter the destiny of their motherland. However, failure was the ultimate outcome of each of their struggles—of the wars of resistance against foreign aggression, the peasants’ revolution of the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom in the mid-19th century, the Westernization Movement designed to adopt Western technology while maintaining Chinese systems, the Reform Movement of 1898 aimed at seeking prosperity, and the Yi He Tuan Movement at the turn of the century which developed into a general anti-imperialist patriotic movement, having begun at the lower strata of society. Lacking a scientific theory, a correct approach, and social forces upon which they could rely, many noble patriots were left to bitterly regret these repeated failures.

Then the Revolution of 1911 erupted in October of that year, leading to the overthrow of the Qing government and the founding of the Republic of China. Monarchical dictatorship, which had ruled China for more than 2,000 years, was finally brought to an end. However, the Revolution of 1911 led by Dr. Sun Yat-sen did not change the semi-colonial and semi-feudal nature of Chinese society or the miserable fate of the people. It was unable to accomplish the historic task of realizing national independence and the people’s liberation. Yet it did pioneer a national democratic revolution in modern Chinese history in the truest sense of the term, opening the floodgates to progress and promoting the spread of democratic and republican ideas. A great wave of intellectual emancipation was sparked, and social change swept the country under the tremendous influence of the revolution, permanently undermining the stability of reactionary rule.

Reality, however, can sometimes be incredibly cruel. The fruits of the 1911 Revolution were seized by the Northern Warlords led by Yuan Shikai, with imperialist support. In a matter of just months, the nascent bourgeois republic had perished. After the death of Yuan Shikai, the Northern Warlords split into the Zhili, Anhui, and Fengtian cliques. Under the manipulations of imperialists, the country was thrown into a state of internecine warfare between various warlord regimes. Under the autocratic rule of the feudal warlords, China was reduced to a semi-colonial, semi-feudal society.

The immense efforts and innumerable sacrifices of the revolution yielded nothing more than a faux republic. After the Revolution of 1911, China tried various forms of government, including a return to monarchy, a parliamentary system, a multiparty system, and a presidential system. Various political forces and their representatives came to the fore, but none could pinpoint the right solution that would change the nature of old Chinese society and transform the fate of the Chinese people. As a result, China remained fractured, impoverished, and weak. Foreign powers were still running roughshod over the country and profiting at its expense, and the Chinese people continued to live in misery and humiliation.

History had shown that without the guidance of advanced theories, and without the leadership of advanced political parties that were armed with these theories and were willing to follow the trend of history, shoulder its heavy responsibilities, and make great sacrifices, the Chinese people would not be able to defeat the various reactionary factions that oppressed them, and the Chinese nation would not be able to change its fate of oppression and subjugation.

China needed a force to lead the mission of national rejuvenation. This assignment would fall on the shoulders of China’s working class, the representative of the advanced productive forces.

I'm almost certain this has been linked here before but i'm posting this again for reference since i found myself needing quick access to a compilation of sources like this, and it can get tiresome having to do the same research over and over again when debunking anti-communist talking points. Hopefully others find it useful as well, and if you haven't gone through this doc before give it a read, you may learn something new.

Saw this post (https://lemmygrad.ml/post/4110233) about China's Cultural Revolution and remembered my project to transcribe my copy of "A Concise History of the Communist Party of China" (ISBN 978-7-5117-3978-0). The book is an English translation of the Chinese book 中国共产党简史, translated by the Institute of Party History and Literature of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China, and published by the Central Compilation & Translation Press. There is another English edition published by ACA Publishing Limited which I have not read, but I assume it's basically the same.

The Chinese edition is available to read online at one of the CPC's online learning platform 学习强国: https://article.xuexi.cn/articles/pdf/index.html?art_id=1514845518710518863

The book has 10 chapters and around 700 pages, each chapter has around 5 to 10 sections for a total of 70 sections. I'm thinking of posting one section at a time every 5 days so as to not overwhelm some readers, and to get the entire book posted over the span of a year. This can change accordingly as we progress. I am typing the contents out manually into LibreOffice Writer so that they can be exported as a pdf or epub document.

This first post will be special and start from the part about the Cultural Revolution, this is not the entire section but a good enough excerpt to summarize the Cultural Revolution. The next post will start from Chapter I and continue in the order as written in the book.

(On the issue of copyright, I am certainly violating some laws but...)

Chapter VI

Explorations and Setbacks in Socialist Development

3. Socialist Development amid Twists and Turns

The Occurrence of the Cultural Revolution and Difficulties in All Aspects of Work

(pg. 264-267)

The Cultural Revolution was set in motion in 1966, just as China was overcoming grave economic difficulties, completing a readjustment of its economy, and launching its Third Five-Year Plan for national economic development.

The occurrence of the Cultural Revolution was due to complex social and historical reasons of both domestic and international nature. For a long time after the founding of the People’s Republic, China faced a severe external environment. The imperialists were hostile to China and imposed a blockade on it for a long period, having pinned their hopes for “peaceful revolution” on the PRC’s third and fourth generations. Meanwhile, the Soviet Union also put great pressure on China, following the deterioration of Sino-Soviet relations. Such an external environment had a great impact on the Party’s well-founded judgements regarding the domestic political situation and its determination of the central tasks and policies of the Party and the state. Having coming through a long and brutal war, the CPC transitioned immediately into the stage of socialism, without having first gained a proper understanding of how to carry out socialist development in a country that was economically and culturally underdeveloped, or having made adequate ideological preparations for such an undertaking. In the period of revolutionary war, the Party had accumulated a great deal of experience in class struggle, experience which people applied and copied all too easily when it came to judging and handling the new problems of socialist development. As a result, they saw problems that were unrelated to class struggle as being part of the class struggle. They viewed the class struggle as being dominant when it was in fact much more limited, and they continued to resort to large-scale political movements as the solution to this problem.

In May 1966, the enlarged meeting of the Political Bureau of the Central Committee adopted the “May 16 Circular,” which pointed out that “the bourgeois representatives who have infiltrated the Party, the government, the army and various cultural circles are a group of counter-revolutionary revisionists who, once conditions are ripe, will seize power and change from the dictatorship of the proletariat to the dictatorship of the bourgeoisie.”

In August, the 11th Plenary Session of the Eight Party Central Committee adopted the Decision of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China on the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, proposing that “the focus of this campaign is to rectify those in power in the Party who have taken the capitalist road.” The convening of these two meetings signified that the Cultural Revolution had begun in earnest. Following this, the country was engulfed by the Red Guard movement.

From January 1967 onward, the Cultural Revolution entered the stage of an all-out grab for power, and began to move very quickly toward a phase of “overthrowing all,” and even full-scale civil war. Around February, Tan Zhenlin, Chen Yi, Ye Jianying, Li Fuchun, Li Xiannian, Xu Xiangqian, Nie Rongzhen, and other revolutionaries of the older generation moved to sharply criticize the erroneous practices of the Cultural Revolution at different meetings. However, their actions, which were labeled the “February adverse current,” were suppressed and attacked.

By September 1968, revolutionary committees had been established nationwide. To some extent, this helped stop the anarchism that was rampant in the early days of the decade-long Cultural Revolution. In October, under extremely abnormal circumstances within the Party, the enlarged 12th Plenary Session of the Eight CPC Central Committee announced the decision to “expel Liu Shaoqi from the Party forever and remove him from all posts he holds in and outside the Party.”

The Ninth National Congress of the CPC, convened in April 1969, further systematized and legitimized the erroneous theory and practice of the Cultural Revolution. Between 1970 and 1971, a plot to seize supreme power was carried out by a counter-revolutionary group led by Lin Biao, which culminated in the staging of a counter-revolutionary armed coup. The incident signaled the failure of the Cultural Revolution in both theoretical and practical terms.

In 1972, Zhou Enlai issued a repudiation of ultra-Left thinking, which led to significant improvements in all areas of work. The Tenth Party Congress held in August 1973 continued to affirm the political and organizational lines of the Ninth Congress. After the Tenth Congress, Jiang Qing, Wang Hongwen, Zhang Chunqiao, and Yao Wenyuan formed the Gang of Four that would attempt to seize supreme power of the Party and the state.

In January 1975, the First Session of the Fourth NPC reaffirmed the goal of achieving the modernization of agriculture, industry, national defense, and science and technology in the 20th century and appointed Zhou Enlai as premier and Deng Xiaoping as first vice premier. This gave Chinese officials and people who had suffered during the repeated upheaval hope for the Party and the state.

The main considerations in launching the Cultural Revolution were to prevent the restoration of capitalism and seek China’s own way of building socialism. As a leader of the ruling proletarian party, Mao Zedong constantly observed and thought about the real life problems of the emerging socialist society. He paid great attention to strengthening the Party and the people’s power, which had been developed with such difficulty, remained highly alert to the danger of capitalist restoration, and made continuous explorations and struggled tirelessly to eliminate corruption, privilege, and bureaucratism in the Party and the government. However, a weak understanding of the laws of socialist development and an accumulation of “Leftist” mistakes in theory and practice meant that many of the right socialist development ideas were never implemented, which eventually resulted in civil unrest.

The Cultural Revolution lasted for ten years and caused the Party, the country, and the people to suffer the longest, most extensive, and most costly setback since the founding of the People’s Republic. The Party’s organization and state power were brutally persecuted, and democracy and the rule of law were trampled on, as the entire country sank into a grave political and social crisis. The Cultural Revolution was in no sense a revolution or a period of social progress. It was a period of civil strife that was erroneously initiated by the leadership and exploited by counter-revolutionary groups, with disastrous effects for the Party, the country, and the people. It left behind extremely painful lessons.

During the Cultural Revolution, the Party and the people never stopped fighting against “Leftist” mistakes. It was the resistance of Party members, workers, peasants, PLA members, intellectuals, and cadres at all levels that limited the damage of the Cultural Revolution. Progress was still made in some important areas of socialist development, and the nature of the Party, the people’s political power, the people’s armed forces, and society as a whole remained unchanged.

This time we're reading chapter 7 of Capital Volume 1. Participation welcome at any time, not just on the weekend of week 14, either in this thread or in our Matrix room (see this post for instructions on how to join)

This time we're reading chapter 6 of Capital Volume 1. Participation welcome at any time, not just on the weekend of week 12, either in this thread or in our Matrix room (see this post for instructions on how to join)

the NIEO as like a plan by the UN, i have no idea what it is and its effects.

This time we're reading chapters 4 and 5 of Capital Volume 1. Participation welcome at any time, not just on the weekend of week 10, either in this thread or in our Matrix room (see this post for instructions on how to join)

I have to deal with liberals asking about this and i gotta say i don't know enough to be sure about my answer

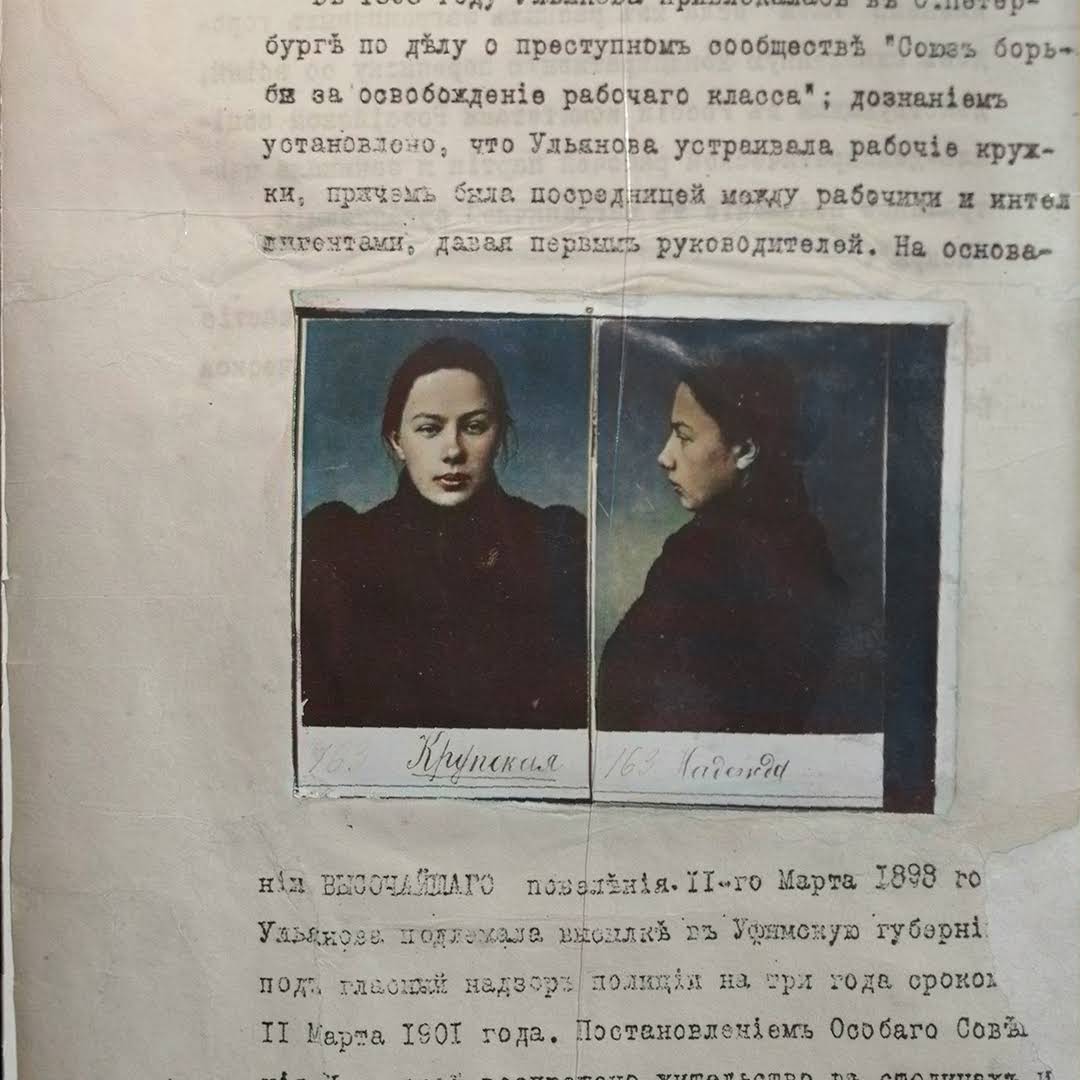

Nadezhda Konstantinovna Krupskaya was born on this day in 1869.

Do you know about Krupskaya's legacy beyond being “Lenin’s wife”?

Krupskaya’s early involvement in Marxist student societies gave her an understanding of the struggles and injustices of working-class people. She dedicated almost 50 years to the party and revolutionary transformation of society.

Krupskaya played a vital role in organizing the underground conspiratorial network supporting the Bolsheviks during the lead-up to the 1917 Revolution, coordinating secret Bolshevik organizers throughout the Russian Empire.

After the revolution succeeded, Krupskaya was instrumental in organizing the Soviet education and library systems after the revolution. Her pedagogical legacy encompassed all aspects of education policy, including teacher training, adult education, and eradicating illiteracy.

Her work in education policy improved the lives of millions of people and ensured that the principles of socialism were instilled in the next generation.

Despite being often minimized as simply Lenin’s wife, her partnership with Lenin was important, but her efforts and contributions to the Marxist-Leninist cause were revolutionary in their own right.

Source: @redstreamnet on YouTube

This time we're reading the rest of chapter 3 of Capital Volume 1. Participation welcome at any time, not just on the weekend of week 8, either in this thread or in our Matrix room (see this post for instructions on how to join)

GenZhou

GenZhou: GenZedong Without the Shitposts(TM)

See this GitHub page for a collection of sources about socialism, imperialism, and other relevant topics.

We have a Matrix homeserver and a Matrix space (shared with GenZedong). See this thread for more information.

Rules:

- This community is explicitly pro-AES (China, Cuba, the DPRK, Laos and Vietnam)

- No ableism, racism, misogyny, transphobia, etc.

- No pro-imperialists, liberals or electoralists

- No dogmatism/idealism

- For articles behind paywalls, try to include the text in the post

- Mark all posts containing NSFW images as NSFW (including things like Nazi imagery)

- Unserious posts will be removed (please post them to /c/GenZedong or elsewhere instead)