this post was submitted on 14 Jan 2024

660 points (98.4% liked)

People Twitter

8341 readers

2347 users here now

People tweeting stuff. We allow tweets from anyone.

RULES:

- Mark NSFW content.

- No doxxing people.

- Must be a pic of the tweet or similar. No direct links to the tweet.

- No bullying or international politcs

- Be excellent to each other.

- Provide an archived link to the tweet (or similar) being shown if it's a major figure or a politician. Archive.is the best way.

founded 2 years ago

MODERATORS

you are viewing a single comment's thread

view the rest of the comments

view the rest of the comments

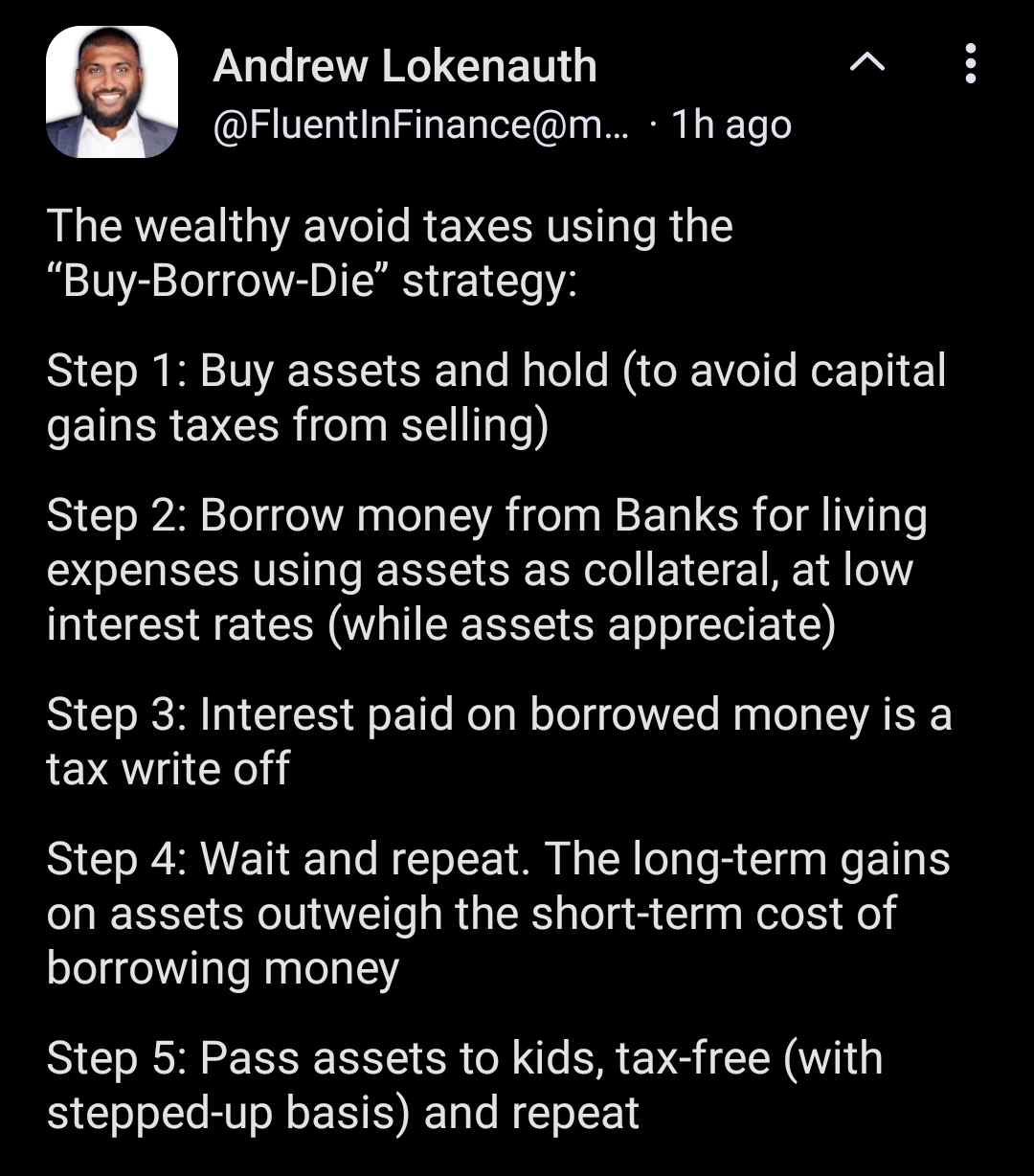

The investment assets can be assumed to appreciate at, say, 7% (reasonably accurate historical US stock market performance). The loan is at a lower interest rate (let's say 3%, which is a number I just pulled out of my ass).

So what they do is take out a loan secured against their investments (which is why it doesn't require having an income to get approved), get a huge lump sum of cash and put that in their bank account. They make payments on the loan by drawing down that lump sum (along with their living expenses or whatever else they want to use the money for). Since the interest rate is >0%, obviously they would run out of money before paying the loan back, right? Well, that's the trick: by the time that happens, their assets have appreciated enough to have enough collateral to get another loan, so they rinse and repeat.

Note that the last line ("assets have appreciated enough to have enough collateral to get another loan") implies that these loans are relatively small compared to the assets backing them. I'm not going to bother doing any actual math, but basically this strategy only works if the expenses you want to cover are some single-digit percentage of your asset value. In other words, if you wanted to borrow $50k/year, you would need more than $1M in assets.

You do this loan thing instead of just living off the dividends because withdrawing the dividends from your investment account incurs capital gains taxes, while getting a loan doesn't.

So they just pull loans in succession, each time large enough to pay the remainder of the prior loan. Meanwhile the assets continue to appreciate, giving more security against the also increasing (but slower) loans.

When does the loan train eventually stop and get paid up? Death doesn't usually wipe them out, but I guess liquidate just enough to pay the debt and the remainder goes to inheritance?

Why pay the remainder of the previous loan? Let those go to maturity.

And yes, the loan train ends at death, and assets are sold to pay them. But since they're dead, they don't pay capital gains on it, the basis (original value of the investments) is stepped up to the current value and the total amount is hit with inheritance taxes, which are usually a lot lower than the income or capital gains tax rate they would otherwise have (income taxes would be 20% for capital gains and 30+% for regular income tax):

The "tax writeoff" is a reduction in the taxable basis for the inheritance. So some quick math:.

If they paid these off the day before they die, it would cost 20% of $5M, or $1M, and then 18% on the other $90M ($16.2M), for total taxes of $17.2M (heirs inherit $73.8M). If they wait until they die, it's 18% of $90M, so they avoid the capital gains tax entirely, so the total inherited amount is ~$74.8M. The difference is probably bigger since that 18% is the top rate and depends on who is inheriting.

I hope that makes sense.

The system really is rigged by the rich to keep them getting richer. That's wild, thank you!

Yup, that's what's called a loophole. If we just set inheritance taxes to the same as capital gains rates, the loophole would effectively be closed.

Well yeah. Of course the people making the laws are going to write them in their favor.

Wouldn't they need to pay the full loan by maturity date? Or are they getting loans with no maturity date?

No, they pay the loan balance throughout the term of the loan. For example, for my mortgage, my final payment is the same as every other payment, it's just the point as which my debt reaches $0.

However, they're probably getting margin loans, which have no maturity date. With a margin loan, you just pay interest in the loan, with nothing going to principle, so they'd just keep that same loan until they die (rates change with the market).

It's probably a mix of both.

Great explanation.

I was surprised that the loan is paid back after the assets get the stepped up basis, and not at the original basis.

Yup, estate tax uses stepped up basis, and fed tax is taken out first, so every other debt will use the post-tax amount.

Fun fact to compare to stock market.

The housing market in Vancouver BC has appreciated at an average return of more than 15% every year for the last nearly 30 years.

Where are you getting a loan for 3% while the stock market is performing at 7%? I always see these arguments, but borrowed interest is almost never lower than gains. That's why step 2 of any worthwhile financial plan is always "pay off your credit cards and high interest loans", right after "save enough for an emergency fund". "Invest your money" doesn't come until a few steps later.

Banks will happily take 3% risk free from someone sufficiently wealthy given the associated relationship benefits: a multi-millionaire or billionaire is probably going to hire that bank for wealth management and pay fees, etc, etc.

I'll have to take your word for it, I guess. It'll be a long time before I have a million dollars cash.

That's true for most folks, and is why it's so hard for people who aren't ultra wealthy to understand just how different the world is when you have that kind of wealth; a world where the law and the financial system and the basic experience of the economy is completely and utterly different due to the power and influence that wealth brings.

Heck, most people can't even truly grok the scale of the difference between an average person and a multi-millionaire or billionaire. The human brain just doesn't process large numbers like that well.

I'm far from rich, but I do have a paid off house in a low CoL area, and a have decent chunk of retirement savings put away, and even then I get different treatment: better credit cards, better loan products, etc. The industry calls it "qualifying" but what it really is is monetary gatekeeping.

It's particularly weird having grown up relatively poor because I've lived the shift and can see how expensive it was to be poor, and how relatively easy it is for the rich to get richer.

¯\_(ツ)_/¯ Presumably billionaires get offered exceptionally favorable terms that aren't available to the general public, I guess?